According to Eurostat, Romania observed 13 of the 14 indicators set for the scoreboard of the macroeconomic situation in the EU member states last year.

According to Eurostat, Romania observed 13 of the 14 indicators set for the scoreboard of the macroeconomic situation in the EU member states last year.

The other countries that have reached this level of compliance were Poland, Sweden, Estonia, Austria and Malta.

On the opposite side was the Cypriot economy, which met only 7 of the 14 criteria required by the EU.

Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure (abbreviated MIP) is a monitoring mechanism that aims at identifying early risks of macroeconomic instability in the country and correcting them.

Romania hardly obtained a stable position in recent years, by meeting almost all the criteria required (there was no way to achieve the net investment position in the context of foreign investments which could not be offset by Romanian capital placements abroad) but the trend of indicators is not encouraging for future developments.

What the scoreboard is

The scoreboard on the evolution of an EU national economy uses 14 performance criteria to warn about potential macroeconomic stability issues. Serious deviations can be the basis of a more in-depth analysis for states that register values exceeding the prescribed theoretical thresholds.

Apart from the preventive side, the MIP also has a corrective side, transposed into the Excessive Imbalance Procedure. Within this procedure, there are recommendations made for gradual measures aimed at bringing key indicators back within the permissible area, which can go as far as to impose sanctions for states that repeatedly violate the recommendations.

The mechanism for monitoring potential macroeconomic problems was established in December 2011 as part of the so-called “six-pack” legislative package. The assessment on meeting these fixed thresholds is based on an analysis that takes into account the moment correlations, with the separation of punctual deviations from those having the potential to trigger systemic shortcomings.

To be noted, the European Commission can adopt preventive recommendations for member states according to Article 121.2 of the EU Treaty, even from the early stages of imbalances, before they develop. Recommendations can be made at the end of May each year, in the context of the so-called European Semester, which is used for coordinating the economic and budgetary policies at the EU level.

A member state that is subject to the macroeconomic imbalance procedure will need to submit a corrective action plan with clear objectives and deadlines. The implementation of this plan will be followed up and recorded in periodical reports. A first failure to achieve the objectives will be penalized by establishing an interest-bearing deposit that can be turned into fine.

Indicators on the dashboard and compliance with thresholds imposed

The 14 indicators initially set for the scoreboard are:

External and competitiveness imbalances:

-

The average balance of the current account over the past 3 years (values allowed between -4% of GDP and + 6% of GDP)

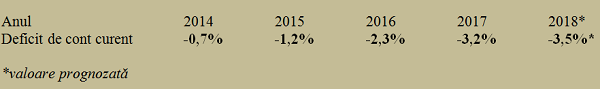

Romania still has an honourable value (-2.2% of GDP from -1.3% of GDP a year ago), although the deterioration trend in this indicator is quite clear, as we can see in the table below:

*

- Year

- Current account deficit

*

It is noteworthy that, out of the six countries that do not comply with this criterion, four appear with a too large surplus resulting from the foreign exchanges (Denmark with + 8.1%, the Netherlands with + 8.3%, Germany and Malta with 8.4% each). At the opposite end is the UK, which will leave the EU in 2019 (-4.6%) and Cyprus (-5%).

-

Net international investment position (liability stock below 35% of GDP)

Not less than 13 EU countries (including Romania, with -47.7% of GDP) fail to meet this criterion. The explanation is given by the consistent foreign investment and relatively low own investment in other countries. We have a slightly weaker level than Bulgaria (-42.8% of GDP), but much better than Ireland (-149.3%), Greece (-142.5%), Cyprus (-121.5%), Portugal (-104.9%) or Spain (-83.8%).

On the other hand, if we exclude the smallest EU member state, Malta (+ 62.6%), the Netherlands has the largest investment position in the positive range (+ 59.7% of GDP), along with Denmark (+ 56.3% of GDP), Germany (+ 54% of GDP), Belgium (+ 52.6% of GDP) and Luxembourg (+ 47% of GDP).

-

The actual real exchange rate variation in the last three years

compared to 42 partner countries in terms of foreign trade (between -5% and + 5% for the Eurozone and between -11% and + 11% for the rest of the EU member states).

Only one country was in 2017 outside the limits required, within the negative range (Ireland, -6.2%) compared to three countries, just a year ago. Romania was at a level consistent with the Non-Eurozone, which would have not been acceptable though in the Eurozone, with a negative value of -5.5% on a trend given by values of -2.5% in 2016 and + 2.7%, recorded in 2015.

-

The share of exports in global exports should not decline by more than 6% in the last five years.

Only one EU member country did not meet this criterion, Greece (-10% but improving from -19% in the previous year). In spite of the chronic foreign trade deficit (almost– EUR 13 billion last year), Romania did very well at this indicator, with + 37%. This is the best performance within the EU, after Ireland (+ 64.4%).

In other words, exports went well, but we should have capitalized much better on this asset instead of wasting it with a too fast growth rhythm in domestic demand. That led to an import rhythm above the otherwise very good exports. Of course, there could also be the question of prices at which imports needed to increase exports have been made, as well as the value added locally.

-

Nominal unit labour costs

(expressed as a ratio between the average remuneration of an employee and the real GDP related to the number of persons employed) below 9% for the Eurozone countries or 12% for the rest of the EU member states, in the last 3 years.

The four countries that did not meet this requirement are the Baltic countries (Latvia 14.7%, Lithuania 16% and Estonia 12.4%) plus Bulgaria (13.6%). With a provisionally estimated value of 11.9%, Romania nearly missed to avoid the 12% fateful threshold, but exceeding it seems to be almost inevitable after latest developments in the area of the minimum national wage and the budget sector.

In the year preceding the one analysed, we were at half the level of 2017 (that is, only 6% compared to 11.9% now), around the central European group to which we should compare, from the perspective of the currency regime and the requirements for joining the Eurozone (Hungary + 6.7%, the Czech Republic + 5.9% and Poland 4.5%).

Internal imbalances:

-

Increase in real house prices (below 6% per year)

The number of countries that did not meet this requirement returned to six, which is the same as two years ago, after a temporary increase in 2016 to ten. With a deflated rhythm of only 4% in relation to the index built based on 2015, Romania easily complied with the requirement, unlike Ireland (+ 9.5%), the Czech Republic (+ 9.1%), Portugal (+ 7.9%) or, much closer to the threshold, Slovenia, Bulgaria (+ 6.2% each) and the Netherlands (+ 6%).

-

Consolidated private credit flow (below 14% of GDP)

All 28 countries had values that are in line with the requirement, and Romania recorded the value of +1.7%.

-

Private sector debt (below 133% of GDP)

12 countries do not meet this requirement. Private sector’s over-indebtedness is evident in many Western economies: Luxembourg (322.9%), Cyprus (316.3%), the Netherlands (252.1%), Ireland (243.6%), Denmark (204%), Sweden (194.4%), Belgium (187%), the UK (169%), Portugal (162.2%), France (148.2%), Finland (146.4%) and Spain (138.8%).

Romania was positioned far below such values, with the lowest value in the EU – only 50.8%, on a downward trend compared to previous years (55.8% in 2016 and 59.1% at the end of 2015). For reference, we mention the values for Bulgaria (100.1%), Poland (76.4%), Hungary (71.4%) and the Czech Republic (67.4%).

-

Public debt (less than 60% of GDP)

With 35.1% of GDP by the European methodology, we are well below 60% of GDP and on a sharply decrease after 37.6% registered in the previous year, at an indicator that raises the biggest problems at the EU level. Not less than 15 states fail to meet this criterion, including Germany, which is on a strong downward trend (63.9%, from 68.1% in the previous year).

However, we should be somewhat more attentive to this indicator, because of the increasing trend in public debt financing costs. Costs that make a tighter limit more advisable for Romania, estimated at no more than 45% of GDP. That would impose a much lower budget deficit and a better management of public funds.

-

Average unemployment rate (the average of last three years below 10%)

Only seven countries do not meet this criterion (Greece 23.6%, Spain 19.6%, Croatia 13.5%, Cyprus 13%, Italy 11.6%, Portugal 10.9% and France 10%) compared to 12 states just a year ago. Notice where these countries are located within the EU and what origins they have, although, favoured by those who leave to work abroad, we have 5.9% in the European statistics.

-

Total liabilities of the financial sector, non-consolidated (less than 16.5%)

Almost all EU states fall within this limit, except for the Czech Republic (22.9%) and Slovakia (17.9%). We were at a reasonable level of 8.1%, but it should be noted that we are coming from + 4.1%, two years ago.

Employment indicators

-

Total activity rate for population aged between 15-64 years (change on three years below -0.2%)

The situation looks well at the level of all member states, with three small exceptions, in terms of the country size or the distance to the threshold: Luxembourg (-0.6%), Cyprus (-0.4%) and Spain (-0.3 %). With a level of + 1.6%, Romania has an honourable value, more than double the previous one (after + 0.7% in 2016).

-

Long-term unemployment as % of the active population aged between 15-74 years (change on three years below 0.5%)

Only one state has not met, which was a near miss, this requirement: Luxembourg (exactly 0.5%). Romania appears in a relatively good position, with -0.8%.

-

Youth unemployment as % of the active population aged between 15-24 years (change on three years below 2%)

All member states have succeeded not only in meeting this criterion but also in coming up with negative values, which means the decrease in youth unemployment. Romania has an honourable value of -5.7% (from -3.1% in the previous year).

*

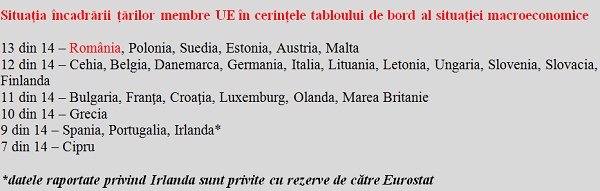

- Situation of EU member countries in meeting the requirements of the macroeconomic scoreboard

- 13 of 14 – Romania, Poland, Sweden, Estonia, Austria, Malta

- 12 of 14 – Czech Republic, Belgium, Denmark, Italy, Lithuania, Latvia, Hungary, Slovenia, Slovakia, Finland

- 11 of 14 – Bulgaria, France, Croatia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, the UK

- 10 of 14 – Greece

- 9 of 14- Spain, Portugal, Ireland *

- 7 of 14 – Cyprus

- * Eurostat is cautious about the data on Ireland

*

All in all, we have achieved a good performance in 2017 but with worsening prospects in the future, contrary to the general trend recorded in the EU member states in the two neuralgic points which can destabilize, only by themselves, the whole fabric of the Romanian economy, despite the excellent position presented by Eurostat.

Potential weaknesses are the foreign deficit and the labour costs, which are in fact in relation to each other at the level of the policy on incomes, increased too rapidly compared to the labour productivity evolution and in an unbalanced manner favouring areas that do not directly contribute to the production activity. Last, but not least, we will have to pay attention to the evolution of the effective real exchange rate, respectively the competitiveness at the international level.