Romania climbed last year on the penultimate position among the EU member states in terms of the productivity of resources in the economy, after Bulgaria, according to data released by Eurostat.

Romania climbed last year on the penultimate position among the EU member states in terms of the productivity of resources in the economy, after Bulgaria, according to data released by Eurostat.

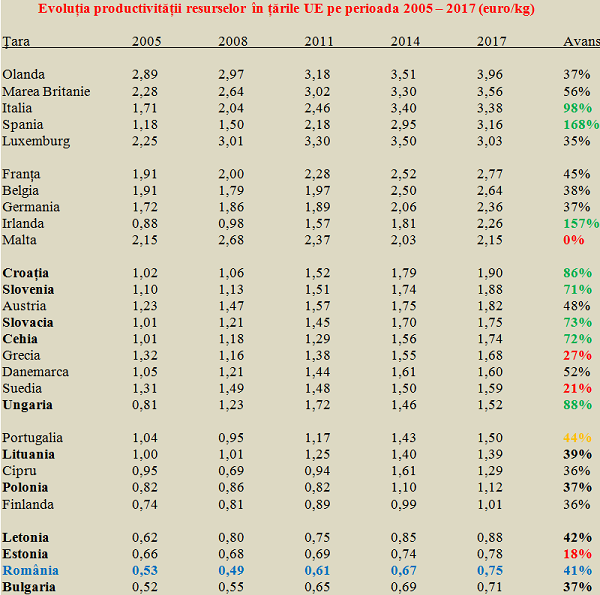

The score of the duel between European laggards has changed from 0.73 euro/kg – 0.64 euro/kg in favour of our neighbours from the south of the Danube in 2016, to 0.75 euro/kg – 0.71 euro/kg for us, in 2017.

However, with only 0.75 euro/kg of raw material used in 2017, we were at a considerable distance from countries like the Netherlands (3.96 euro/kg), the UK (3.56 euro/kg), Italy (3.38 euro/kg) or Spain (3.16 euro/kg). And we remain somewhere at less than half compared to former socialist countries in Central Europe.

Beyond the structure of the economy, more or less based on services, the resource productivity indicator shows the capability to use raw materials as efficiently as possible.

That depends on the product nomenclature as well as on the technologies used, and the influences are seen in labour productivity and environmental pollution. That, with direct consequences in a faster or a slower development as well as more or less sustainable.

*

The productivity of a country’s resources is measured by dividing its GDP by domestic consumption of materials (from domestic production plus the balance between imported and exported raw materials). On the level of resource productivity, the European hierarchy looks significantly different from the standard of living situation, with the UK, Italy and Spain occupying dominant positions, at a great distance from the rest of the platoon and with the northern countries Denmark, Sweden and Finland at the bottom of the ranking.

Productivity growth rhythm in recent years and European updated ranking

The champion in terms of resource using since in 2005 was Spain, which has achieved a very strong improvement (+168%) of this economic indicator and has climbed from the mediocrity level to the top of the European list.

It was followed by Ireland (+156%), which went from a similar level to Hungary and Poland and came close to Germany, Belgium and France.

*

- Evolution of resource productivity in EU countries between 2005 -2017 (euro/kg)

- Country

- The Netherlands

- UK

- Italy

- Spain

- Luxembourg

- France

- Belgium

- Germany

- Ireland

- Malta

- Croatia

- Slovenia

- Austria

- Slovakia

- The Czech Republic

- Greece

- Denmark

- Sweden

- Hungary

- Portugal

- Lithuania

- Cyprus

- Poland

- Finland

- Latvia

- Estonia

- Romania

- Bulgaria

*

Resource productivity went down in Romania between 2005 and 2008, that is, just in the boom years (only the Greek economy has experienced a decline in this indicator, with the exception of the conjuncture evolution in Belgium, positioned on an entirely different level).

Later recovery has brought us improvement values similar to the group of Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Bulgaria (Estonia has a situation similar to the unpleasant surprise of Sweden, now overcome at this chapter NOT only by several states from the former Eastern bloc but also by the neighbouring Denmark, which recovered a significant gap).

Eurostat data shows in our case a development model with highly extensive and less intensive features built with more focus on technology consumption and resource use. Hence an important cause of a still relatively low added value of production processes and a potential cause of stagnation in the future at a development level of 70% -80% of the EU average.

Interestingly, including in terms of geographic grouping, the improvement in the resource productivity indicator was roughly double in the group formed by Croatia, Slovenia, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary compared to the above-mentioned group of which we are part. Hence the major objective gap, with Romania competing with Bulgaria to cross a symbolic threshold of 1 euro/kg, reached by countries that are heading to 2 euro/kg since 2005.

This is a positioning that represents an early warning.

Beyond the economic results, which are quite good in terms of quantity, we should be more careful about the quality of growth. Here we are somewhat weaker in terms of real convergence with the EU economies and we are likely to get into a mediocrity blockage of the Portuguese type.