In the first three quarters of 2017, net investment in the national economy amounted to about RON 50 billion, up by 3.6%, compared to the same period in 2016, the National Institute of Statistics announced. This is the effect of a considerable advance in the third quarter when the rhythm climbed to + 10.3%.

In the first three quarters of 2017, net investment in the national economy amounted to about RON 50 billion, up by 3.6%, compared to the same period in 2016, the National Institute of Statistics announced. This is the effect of a considerable advance in the third quarter when the rhythm climbed to + 10.3%.

The good news is that data shows the third year of growth.

The less good news is that investments remained far behind the 7% GDP growth.

And the bad news is that we have just returned to the level of investments (in the first three quarters) registered in 2012. The year in which the GDP was RON 595 billion and not RON 908 billion, as estimated for 2017.

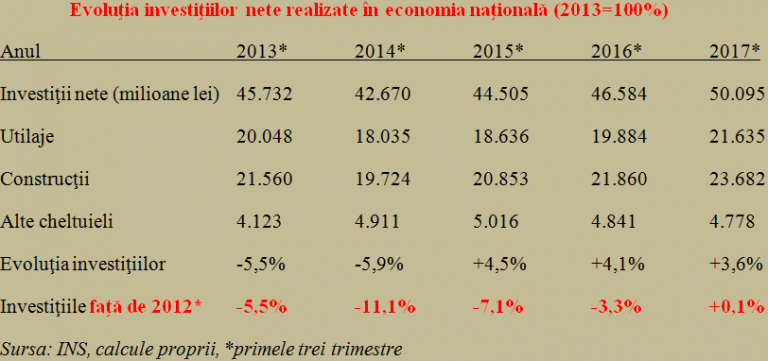

Here is how this indicator evolved over the past five years:

*

- Evolution of net investments in the national economy (2013=100%)

- Year

- Net investments (million RON)

- Equipment

- Construction

- Other expenses

- Evolution of the investments

- Investments compared to 2012

*

Maintaining investments below or at about the same level as in 2012, in the context of the GDP rising from about RON 595 billion to RON 908 billion over the last five years (+53%), is a serious economic policy error, whose effects will inevitably be seen in the future. Without stepping up investment, we shall not be able to cross the range of about 70% to 80% of the average GDP per capita in the EU and we shall find ourselves in the so-called „middle-income trap„.

From this perspective, the considerable increase in investments during the current year would be welcome. The condition is for this trend to be retained by the end of 2017 and in 2018, which is unlikely to be seen because of the budget constraints, to remain within the 3% of GDP deficit threshold, under the pressure of the expenditures riskily engaged for the wages in the public sector and pensions.

*

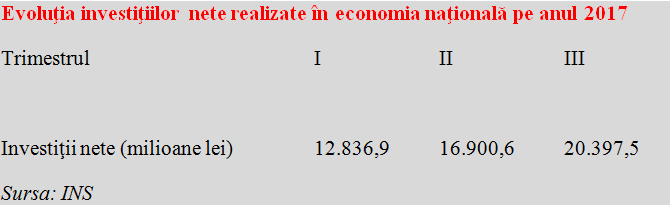

- Evolution of net investments in the national economy in 2017

- Quarter

- Net investments (million RON)

*

The change in the way of placing the emphasis in the economic growth from stimulating the production in times of crisis to the continuous and strong push on the consumption button is becoming a key issue in this context. Which should be reversed and balanced in a fair way by the decision-makers.

The path of just increasing the consumption does nothing but sustains an economic advance that will get suffocated in the medium term, once it will appear the physical and moral wear and tear of the purchased assets of a value capped in nominal terms, and largely left behind the GDP growth.

Unfortunately, the investment effects cannot be seen immediately, but in the years to come, and totally different policy-makers may or may not benefit from the change in approaching the economic policy.

Although, in theory, resource allocation to infrastructure development, acquisition of production assets for modernization and increasing the competitiveness is absolutely desirable, and must be stimulated by the state through adequate policies, the easy allocation way to increase revenues and spreading the resources to consumption can prevail in the social practice.

In fact, sustainable over time, the extra pay can be recovered and represent the basis for future social benefits in the future only by increasing the efficiency of the activity that depends on investment.

In other words, wages and pensions can grow sustainably only by maintaining a solid pace of investment that would generate a robust growth in commodity and service sales that are duly taxed in terms of public finances.

Forcing the pace of the income growth set at the administrative level (in the public sector and in pensions) only allows an increase only for the moment of the living standard, of the „competitiveness” on the demand side (not on the supply side).

If they are clearly above the GDP growth (about three times today), the capability to cover the additional demand from own sources and without strongly increased investments will suffer, which leads to the increase in the share of foreign products that will cover the gap left.

A direct consequence, with small investments relative to the GDP, is that it will be increasingly harder to achieve high growth results. Instead of developing its own economy, the exacerbated demand is driving growth in the foreign economies whose more competitive and sufficient products will come to cover our extra demand.

Therefore, an optimal balance in the allocation of public resources between investments and income growth would be mandatory for systematically and seamlessly reducing the gap with the West. That would be for us to avoid progressively transforming ourselves into an outlet, increasingly dependent on the supplies from abroad.