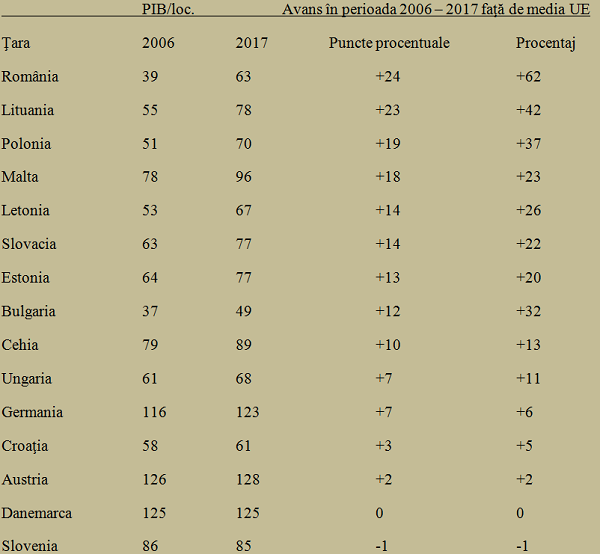

Romania is the EU member state that has benefited the most from EU membership, with an increase in the standard of living expressed in GDP per capita at the standard purchasing power parity (adjusted with the country price levels) from only 39% in 2006 to 63% last year, according to data released by Eurostat.

Romania is the EU member state that has benefited the most from EU membership, with an increase in the standard of living expressed in GDP per capita at the standard purchasing power parity (adjusted with the country price levels) from only 39% in 2006 to 63% last year, according to data released by Eurostat.

The advance of 24 percentage points was above the one recorded by Lithuania (23pp), Poland (19pp, although it was the only country that went through the crisis without a decline in the economy), Malta (18pp, surprisingly positioned among colleagues from the 2004 accession round), Slovakia and Latvia (14 pp.) and Estonia (13 pp.).

*

- GDP/capita Advance in 2006-2017 compared to EU average

- Country 2016 2017 Percentage points Percentage

- Romania

- Lithuania

- Poland

- Malta

- Latvia

- Slovakia

- Estonia

- Bulgaria

- Czech Republic

- Hungary

- Germany

- Croatia

- Austria

- Denmark

- Slovenia

*

Our EU accession round colleague Bulgaria, which started from a GDP/inhabitant level very close to ours (37% of the EU average at that time, only two percentage points below us), managed to advance by only 12 percentage points and is the only country left below half of the EU average, despite its intentions to join the Eurozone.

While the ten-point advance is a solid and sustainable one for the Czech Republic, with a certain approach to the West, Hungary has gained only 7 pp. and saw an increase in the standard of living by only 11% over the past 11 years, after going round in circles since 2014. It has thus achieved only a performance similar to the European driver Germany.

In fact, Germany is the only Western state that has benefited massively from the eastward expansion of the EU, followed from the distance by its sister Austria (+2pp, which ranks, though, slightly higher in the last year’s Eurostat statistics, with 128% of the EU average vs. only 123% in Germany’s case). Only Denmark has also managed not to lose ground to the EU average.

Surprisingly, there is also a state in the former socialist bloc that lost a percentage point to the mobile benchmark of the European average, namely Slovenia, which slightly regressed from 86% to just 85% of this benchmark. It joined several Western states that declined in relative terms, which is a natural result of the higher rhythms of development of new members.

*

- Countries that moderately regressed compared to the EU average (2006-2017)

- GDP/capita Advance in 2006-2017 compared to the EU average

- Country

- Belgium

- Sweden

- France

- Finland

- Portugal

- Netherlands

*

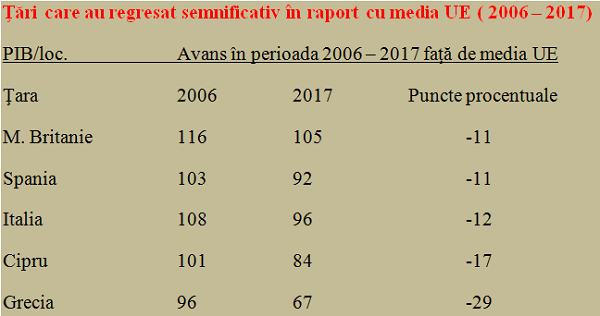

Unlike those countries that were relatively well yet not so well as the EU newcomers, but they had resources to support relatively minor losses in the GDP/capita (a notable exception is Portugal, which declined from where it had not actually the chance to advance, although it is an EU member since 1986 and accessed substantial funds during that time), we also have countries that lost more than ten percentage points compared to the EU average.

The most interesting situation is UK’s one, in fact, the only country that has managed to maintain the level above the EU average, but the negative feeling (caused by those who searched elsewhere for the blame that the EU had no use, on the contrary) brought the surprising vote that would lead to the UK leaving the bloc.

Other two relatively large economies, Italy and Spain, had a performance of pronounced speed loss, which (significantly to us who are also of Latin origins) was caused, to a significant extent, by the socio-cultural coordinates. Their situation has confirmed the assertion that it is not enough to reach a certain level, you also have to maintain there, which is not obtained by itself.

*

- Countries that regressed significantly compared to the EU average (2006-2017)

- GDP/capita Advance in 2006-2017 compared to the EU average

- Country

- UK

- Spain

- Italy

- Cyprus

- Greece

*

This is also the case of smaller countries, not primary cousins, but almost sisters, Cyprus and Greece. The first has lost the target attained in 2006, of reaching the EU average, while the enthusiasm of approaching the same target was so high for the latter that it led to major economic policy slippages and a real collapse, from 96% to just 67% of the EU average.

These are some aspects and experiences at hand, from which we should learn so that we do not repeat the experience of others. Especially that we are, although obviously not British, both Latin and Balkan nationals.

Perhaps we shall succeed though in getting the Latin nature closer to France, and positioning ourselves in the Balkans, in terms of economy, as a sort of Poland, since we started to progress.