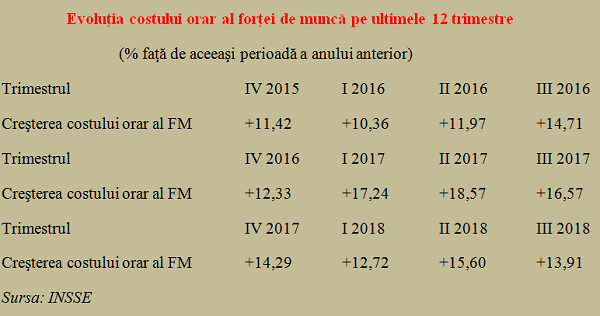

Hourly labour costs grew by 13.91% in the third quarter of 2018 compared to the same period in 2017 (+1.53% compared to Q2 2018), according to INS data.

Hourly labour costs grew by 13.91% in the third quarter of 2018 compared to the same period in 2017 (+1.53% compared to Q2 2018), according to INS data.

It is a slight decrease compared to the previous quarter but above the 12% threshold watched in the non-Eurozone area on the macroeconomic scoreboard centralized at Eurostat for the macroeconomic imbalance procedure.

More importantly, the level of 13.91% has replaced the level of only 7.28% from Q3 2015 in the calculation used in the past three years. That will lead to losing the compliance with this indicator (provisionally announced at 11.9% for Romania in 2017, when we achieved the performance to meet 13 of the 14 macro-stability criteria).

Here’s how the situation is in the past 12 quarters:

*

- Evolution of hourly labour costs in the last 12 quarters (% compared to the same period of the previous year)

- Quarter

- Increase in the hourly labour cost

- Quarter

- Increase in the hourly labour cost

- Quarter

- Increase in the hourly labour cost

*

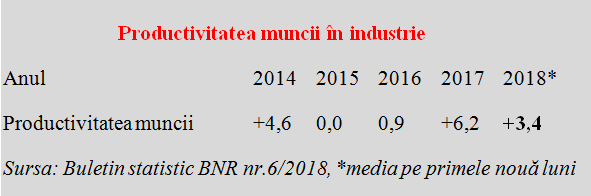

In order to see to what extent the increase in labour cost has been covered by the economic activity, we also present the evolution of labour productivity in the manufacturing industry, the one which can be measured with certainty and to which a correlation should be made in terms of wage increases in order to avoid inducing macroeconomic imbalances.

- Labour productivity in manufacturing industry

- Year

- Labour productivity

- Source: BNR statistic bulletin 6/2018, *average on first nine months

*

For 2017 and the first nine months of 2018, we can easily notice an evolution of the labour productivity close to the GDP growth rate.

Instead, last year the increase in labour costs was about two and a half times higher, and this year, although it relatively dropped, it was three and a half times higher (according to the provisional GDP data).

Without being the end of the world at the moment, not only the major decorrelation between the two indicators raises questions but also the expansion of the difference in the growth rhythm. In addition, precisely the public sector (where measuring the labour productivity is questionable) has taken an advance to the top, while the manufacturing industry has maintained around 10%, alongside hotels and restaurants.

This is how much the labour cost has increased in different sectors of the economy, classified according to international norms:

*

- Quarterly indices of hourly labour cost in Q3 2018 (% compared to Q3 2017, adjusted to the number of working days

- Economic activities Total labour cost

- Health and social assistance

- Education

- IT&C

- Construction

- Manufacturing, construction and services

- Water distribution, sanitation, waste management

- Public administration and defence; social insurance

- Other service activities

- Real estate

- Hotels and restaurants

- Manufacturing industry

- Professional, technical and scientific activities

- Administrative and support services activity

- Retail and wholesale trade

- Transport and warehousing

- Energy, water and gas production and supply

- Arts, entertainment and recreation

- Extractive industry

*

The structure of salary cost increases in the economy, with health and education on top positions in terms of labour cost increases, comes to remedy an older injustice but needs to be properly supported from a budgetary point of view.

Regarding the public administration, it is good that it has dropped to a more reasonable level, below the average, but its position above the manufacturing industry is not quite right.

If we look at the rest of the EU countries, we see that overruns of the 12% level of the average labour cost over the last three years are still only in Bulgaria and the Baltic countries. Which shows that we are dealing with an objective phenomenon, but the careful management of the growth rhythm will remain a medium-term problem.

The proportion of wages in the cost of products has already contributed to a more than six per cent advance in industrial production prices, which is seen in the competitiveness erosion, in a significant increase of the GDP deflator (which adjusts the nominal GDP to the real value) and will manifest in a quite durable way in the consumer prices.