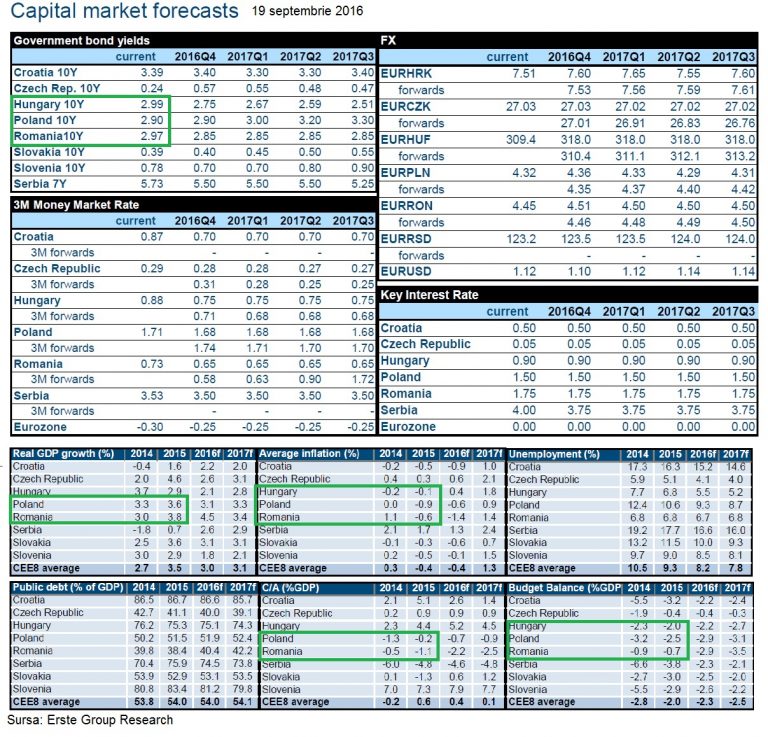

September 2016: The market yield of 10-year Romanian government bonds was 2.97%.

Very good situation: yield was lower by two-hundredths percent (2 basis points, bps) than Hungarian bonds.

Long-term Romanian government loans were only 7 bps more expensive than the Polish ones.

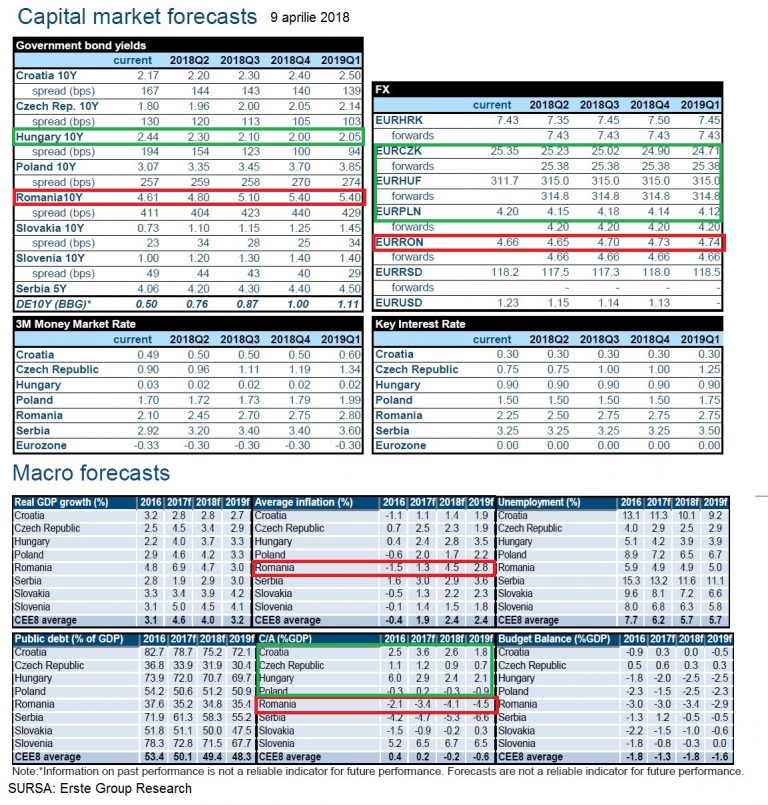

April 2018: The cost of funding by 10-year bonds issued by the Romanian government went up to 4.61% – almost double the one of the Hungarian government, which has declined to 2.44%, according to latest data of Erste Group Research (EGR).

A remarkable evolution was also observed for Bulgarian 10-year bonds, whose yield fell from 2.55% in 2016 to 1.19% now.

Poland, like Romania, borrows at higher costs than in September 2016, but the yield on Polish bonds stopped at 3.07%.

Worse: Romania, the country with the highest economic growth in the EU, is now borrowing at the highest costs in the region, while in September 2016 only the governments of Serbia and Croatia had worse positions on the financial markets.

And we came to this situation in only one year and a half.

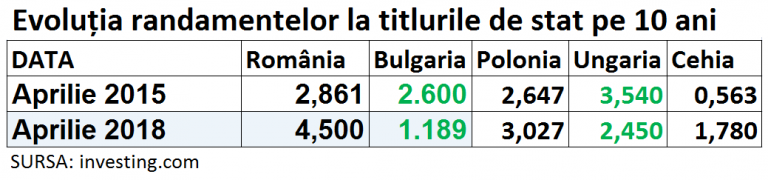

Below, the comparison with the yields (in%) registered three years ago:

*

- Evolution of 10-year state bond yields

- Date

- April 2015

- April 2018

*

The cost of government financing declined in Bulgaria, which is under the rigors of a severe monetary council, and in Hungary, which manages to attract foreign investment despite „illiberal” political messages.

The increases in Poland and the Czech Republic are far less threatening than in Romania.

Evolution of imbalances

The divergent evolution of the Romanian costs of financing compared to the other countries in the region is the expression of differences between macroeconomic (un)balances and, especially between current account, trade and budget deficits.

As early as three years ago, the Romanian Government planned the fiscal relaxation to reach its peak in 2017.

„Wide fiscal relaxation – too much and too good can harm,” the BCR report said on April 23, 2015.

The government had then decided, „following an intense one month promotion campaign“, to bring forward the start of a „four-year plan of fiscal relaxation measures which would have been launched in 2016” and announced at the beginning of April 2015 the VAT cut on all food products to 9%, from 24%.

The relaxation seemed encouraged by an inflation forecast of 0.1% for that year (the average of 2015 was going to be -0.6%), but this was rather the effect of the deflationist threat from the rest of the world and the monetary relaxation policy („free money”), exported by the US and the Eurozone.

Especially under the influence of the external environment, the BNR monetary policy rate had just cut to 2% and it was going to reach, within one month, the historic minimum of 1.75%.

Romania’s current account deficit was only 1.1% of GDP in 2015, the budget deficit was only 0.7%, and the public debt had the lowest share of GDP in the region, 38.4%.

Here are the details:

As early as two years ago, Erste Group Research (EGR) analysts warned that the current account deficit would rise by as much as one percent of GDP if „the monetary relaxation gets out of control.”

As early as two years ago, Erste Group Research (EGR) analysts warned that the current account deficit would rise by as much as one percent of GDP if „the monetary relaxation gets out of control.”

And, it is known, fiscal relaxation has become a „revolution,” whose effects, coupled with the effects of wage increases, the Government no longer knows how to mitigate by ordinances, one more urgent than another.

Current account deficit almost tripled.

April 2018 picture is the following:

The big discrepancies between Romanian (un)balances and those in the region were also noted in the very report of BNR administrators submitted to a Senate committee late last month.

The big discrepancies between Romanian (un)balances and those in the region were also noted in the very report of BNR administrators submitted to a Senate committee late last month.

Only two days before the BNR report submitted to a Senate committee, cursdeguvernare.ro was quoting EGR data that noted the current account discrepancies:

- Czech Republic, Hungary and Croatia are credited with current account surpluses (+ 0.9%, + 2.4% and + 2.6%) in the first quarter of 2018

- Romania with the highest current account deficit rate in the region in 2018, after Serbia (-4.1% of GDP, compared to -5.3% in Serbia).

Now, the threat of an inflation peak rate of 5% in Romania worsens investors’ perspectives who are now less open to granting money, or at higher interest rates, to the Romanian government.

Almost everyone was surprised that BNR postponed the increase of the reference interest rate, while in Poland the first increase could only be applied in 2019, as the inflation is low.

Instead, Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic surprised with an inflation decrease in March, according to Capital Economics:

- Inflation decline was the highest in Poland, where it „plunged from 2.5% y-o-y in November to 1.3% in the last month.”

- In the Czech Republic, it dropped from 2.8% in October to 1.6% y-o-y in February.

- „Hungarian inflation has shrunk from 2.6% in August to 1.9% in February”.

„Low inflation rates occurred despite the mature phase of the economic cycle in the region,” and the analysts mentioned attribute them to some conjunctural decreases especially in prices of food products and fuel.