Romania scored at the end of the first quarter of 2017 not only the highest economic growth among the EU countries (5.7% gross and 5.6% adjusted by Eurostat to ensure the comparability with other states) but also the top position in terms of industrial growth, with a soaring percentage of +15,3% in March versus the previous month (+ 2.6% in comparable conditions, but still the highest position within the EU) and + 10.2% as compared to March 2016, the second position after much smaller Estonia (+ 14.8%).

Romania scored at the end of the first quarter of 2017 not only the highest economic growth among the EU countries (5.7% gross and 5.6% adjusted by Eurostat to ensure the comparability with other states) but also the top position in terms of industrial growth, with a soaring percentage of +15,3% in March versus the previous month (+ 2.6% in comparable conditions, but still the highest position within the EU) and + 10.2% as compared to March 2016, the second position after much smaller Estonia (+ 14.8%).

Basically, we should have been delighted if we had not also exceeded for the first time the EUR 1 billion threshold of the monthly trade deficit and if the balance of the goods segment had not exceeded EUR 2 billion in the first quarter of the year.

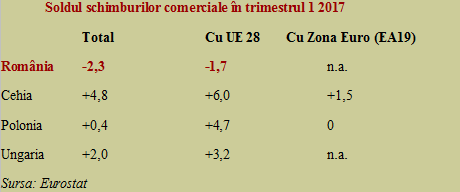

That does not match very well the data registered by our colleagues from the socialist bloc that joined the EU and have the same floating exchange rates regime of the national currencies, the Czech Republic, Poland and Hungary.

*

- Balance of trade exchanges in Q1 2017

- Total With the EU28 With the Eurozone (EA19)

*

All three countries have positive not negative results, like us, in the international commodity trade and manage to register a positive balance within the trade between the EU countries. Based also on the goods delivered to Romania, to which they contribute almost half of the already chronic deficit of the international trade, a deficit to which (unfortunately) we became accustomed.

The difference between us and them is one of COMPETITIVENESS, of an optimal balance between quality and price, a criterion where we continue to be defeated and lose not only on the foreign markets but also on the domestic market.

Unfortunately, this phenomenon tends to become more and more visible as our income increases. The explanation is not surprising at all given the positions of the Czech economy (which has a comparable GDP to ours) and Polish economy (with a GDP more than double).

And face to face with Eurozone

From the perspective of our objective to join the Eurozone (EA 19), we should note that in March 2017 this single currency group saw a surplus of EUR 30.9 billion in the exchanges of goods with other states. But the Czech Republic has a surplus of EUR 1.5 billion in relation to the Eurozone, and Poland has been at zero since the beginning of this year.

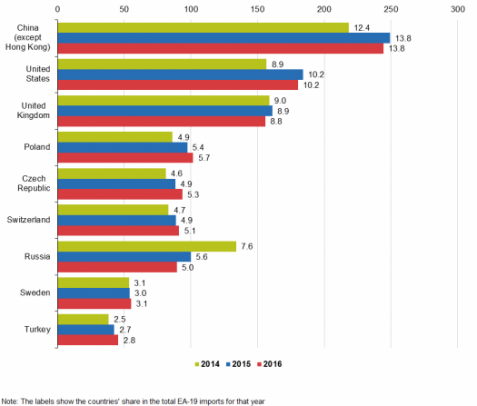

Figure below: Share of EA19 imports corresponding to Euro Zone trading partners

Moreover, the Czech Republic and Poland ranks fourth and fifth in top Euro zone imports after China, the US and the United Kingdom, ahead of Switzerland (see figure), having systematically and substantially progressed in the market share of their goods in the West. We remind that the Czech economy is comparable in size to Romania. But only in size, not also COMPETITIVENESS.

In fact, the Czech Republic and Poland are strongly integrated into the Eurozone, and only the opportunities related to keeping their own monetary policy keep them outside. Otherwise, not only could they join whenever they want, but they would also be among the best performers in terms of competitiveness even within the Eurozone.

Why others do not want to change to euro and why we cannot do that

Why do they not do that yet? That would be a good question for them, but even a better one for us if we knew how to be aware and relate to the economies that are slightly ahead of us. Economies which, although they do not register the same rate of growth, they do not afford either so many budgetary extravagances. The most important aspect is a convergence that will anyway happen whether we want it or not.

This is the convergence of prices, which will get closer to the European average as the access to commodities will become increasingly easier and the minds of the Eastern consumers will adapt to the Western lifestyle.

However, this convergence can happen in only two ways, outside the Eurozone, but with the country’s own monetary policy or within the Eurozone, without being able to use this tool anymore.

The first option would be ideal (which the Czech Republic and Poland adopted by delaying the changeover to the euro), which involves the slight but continuous appreciation of the national currency, with the absorption into productivity and the commodities’ quality increase, of the inherent decrease in price competitiveness. But with long-term benefits in terms of purchasing power and living standards of the whole population, even though people do not immediately see spectacular increases of the nominal salaries or pensions.

Until now, the same as the Czech Republic and Poland, but having the competitiveness gap that remains to be recovered, Romania has also tried to do that. Unfortunately, no matter the performance that our economy would register, there are still some to exaggerate in offering benefits the same as in the saying about selling the bearskin before the bear is caught.

A risky political venture that leaves little room or, if we were to take very seriously a recent official warning, no room for the appreciation of the local currency against the euro in real terms.