Romania undertook, between 2006 and 2016, the most bizarre policy on public funds of all European countries, according to an analysis released by Eurostat. Starting from the last position in terms of the share of budget revenues in GDP, our country struggled hard last year to reduce them even further.

Romania undertook, between 2006 and 2016, the most bizarre policy on public funds of all European countries, according to an analysis released by Eurostat. Starting from the last position in terms of the share of budget revenues in GDP, our country struggled hard last year to reduce them even further.

Only the massive relocation of some multinationals in little Ireland made us lose, under very special statistical circumstances, the position of a European red flashlight to which we would have been fully entitled to due to the utterly irresponsible strategy of permanent tax ease. A strategy based on which we shall ensure not the convergence but the divergence in relation to civilized Europe.

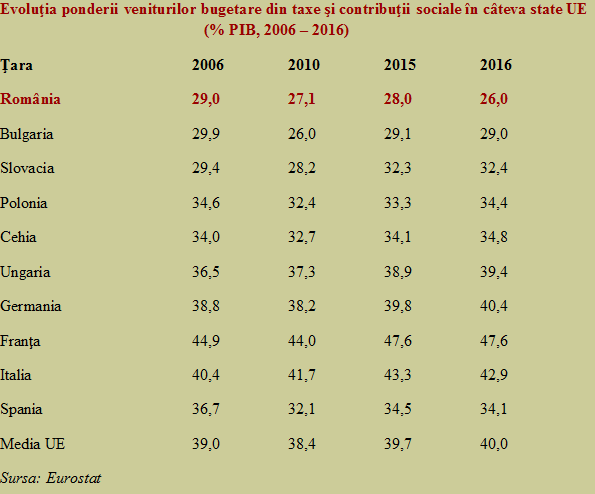

From a minus 10% of GDP in budget revenues from taxes and social contributions compared to the European average just before the EU accession, Romania has reached a disastrous -14% last year, after decreasing the revenue collection by three percentage points in the context of the increase in the overall average by one percentage point (see table).

*

- Evolution of the share in budget revenues from taxes and social contributions in some EU countries (% GDP, 2006-2016)

- Country

*

On this divergent trend in relation to the practice in the Western states that we want to catch up, the ratio of the money available to the Romanian state for health, education, administration, public order, social protection, etc. and the EU average (considering, of course, the proportion of GDP level) fell from 74% to only 65%.

It may seem a little to some people, but within ten years, the increase in the budget revenues needed for us to start on an equal footing with our counterparts that manage public funds has grown from + 35% (correct is the increase needed in taxes) to a fulminant + 54% in 2016. Make the ratio of 100% to 74% and then to 65% and see what result we obtain.

An important mention. Contrary to the established political clichés, the state, basically, does not takes or gives money, but redistributes it. From productive activity or consumption to the areas of which it is in charge (mentioned above) or from one to the other. If you wish, move some of the decision of money use from your personal pocket to the benefit of all.

A state that redistributes a little is inherently a weak state (not in terms of repression but the possibility to provide social services). Lacking the ability to perform at the level of Western societies to which we theoretically aspire, and do not quite agree when it comes to accurately translating them into practice. As we would translate from English, we should put the money where we put the words.

Specific issues: Possible and feasible solutions in European practice

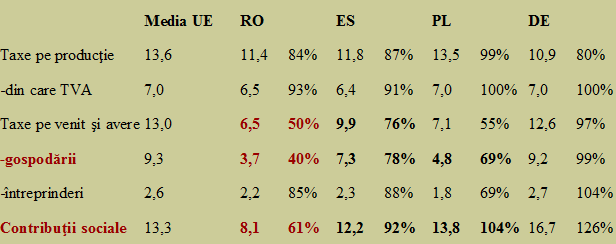

Beyond the eternal and traditional lamentations about our situation, where we cannot do so much with so little, neither public policies without money, let’s look at others and see what we can do. We chose three countries: Spain (because it is Latin, somewhat similar and the only one besides Romania that is below the European average of revenue collection in all areas), Poland (because it comes from the eastern block and is closest to us in terms of the economy size, structure and level of development) and Germany (chosen as a benchmark for its optimized economic and social performance).

*

- EU average

- Tax on production

- – of which VAT

- Tax on income and wealth

- – households

- – companies

- Social contributions

*

If we are to compare the percentages to the European usage, we immediately see the source of problems in public budget financing. Even if we do not agree, we shall have to increase sometime, as soon as possible, taxes on households and social contributions. The dose of them could be of a Polish inspiration and commensurate with the level of the increase in living standards.

The Bulgarian alternative to this Spanish-Polish-German action would be to maintain the taxes mentioned at relatively low values and strongly push the tax on production and VAT (measuring, at the south of the Danube, 114% and 131%, respectively, of the EU average).

The fact that the second option does not seem to be for a long run, beyond our national appetite for VAT evasion, is explained by Germany’s positioning, not at all a Bulgarian one, which applied a strategy of reduced taxes on production (with the VAT collected positioned at the EU average) and boosted social contributions above the European average.

As well as the disguise of Poland, in terms of fiscal policy, as a kind of smaller Germany, by keeping the proportions between the level of development and the taxation share compared to the European average. A model to which our Latin cousins from Spain also get close, except for our unwillingness to have taxes applied at the personal level, which can be explained (interesting note: not as much at the household level but on the social contributions side).