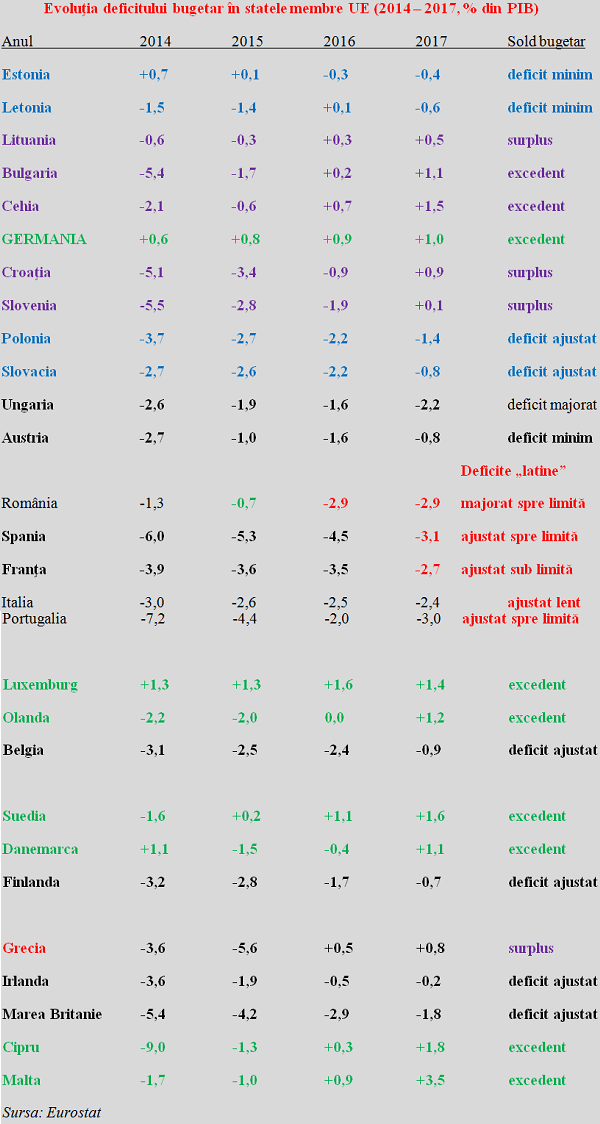

After a successful public finance adjustment before the colleagues within the Eastern bloc, Romania went back significantly toward the budget deficit threshold despite the steady economic growth in the last two years (-2.9% in 2016 and 2017, after -0.7% in 2015).

After a successful public finance adjustment before the colleagues within the Eastern bloc, Romania went back significantly toward the budget deficit threshold despite the steady economic growth in the last two years (-2.9% in 2016 and 2017, after -0.7% in 2015).

Eurostat data position us among the most undisciplined states, in counter-current with the European recommendations and in a spectacular decline from the 7th position in 2015 to 26th in 2017, as a result of the budget implementation in relation to GDP.

Only two EU member states have recorded equal values or slightly higher than the threshold of 3% of GDP imposed by Maastricht criteria, namely our Latin cousins Spain (-3.1%) and Portugal (-3%). But they started in 2014 from much higher levels (-6.0% Spain and -7.2% Portugal) and made an effort to lower the budget deficit.

The same as France, which succeeded, after three years of persistent warnings on the excessive budget deficit, to go down from -3.9% in 2014 to -2.7% in 2017 and go back within the requirements of the financial stability. It should be noted though that France, like Spain, has a public debt of 98% of GDP, which indicates a cultural predisposition for contracting debts.

The other Latin reference, Italy, although below the fateful threshold of 3%, also marked a certain deficit decrease with a projection of -2.4% for 2019. Reported at the EU level for the already very high public debt, maintained at 131% of GDP in the last four years (where Portugal was in 2014 and struggled to fall below 125% in 2017).

*

- Evolution of budget deficit in EU member states (2014-2017, %of GDP)

- Year Budget balance

- Estonia

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Bulgaria

- Czech Republic

- Germany

- Croatia

- Slovenia

- Poland

- Slovakia

- Hungary

- Austria

- Romania

- Spain

- France

- Italy

- Portugal

- Luxembourg

- Netherlands

- Belgium

- Sweden

- Denmark

- Finland

- Greece

- Ireland

- UK

- Cyprus

- Malta

*

In contrast to almost all EU member states, Romania has missed the opportunity of its efforts made for seven years to bring the budget balance within the assumed target of -1% at the structural level through the so-called MTO (medium-term objective) including by increasing budget revenues to more than 35% of GDP (in 2017, we declined to only 30.7%).

With a budget implementation balance of -0.7% of GDP, we were just three years ago very close to the Czech Republic (-0.6% of GDP) and Lithuania (-0.3% of GDP), behind some Northern countries that obtained surpluses (Luxembourg + 1.3%, Germany + 0.8%, Sweden + 0.2% and Estonia + 0.1%).

It should be noted that no less than 13 EU member states recorded in 2017, when Romania continued to sidestep in terms of budget balance within the 3% of GDP threshold despite the record economic growth (almost seven percentage points), a surplus in public budget, on the German model.

Among our former Eastern bloc colleagues, this category included our neighbour of 2015 budget implementation, the Czech Republic (+ 1.5%, which continued the adjustment until it reached the positive range), Balkan states somewhat wiser like Bulgaria (+ 1.1%), Croatia (+ 0.9%) and Slovenia (+ 0.1%), which were joined by Estonia (+ 0.1%).

Baltic Estonia (-0.4%) and Latvia (-0.6%) went with minor deficits after having had small positive values in previous years while Slovakia (-0.8%) and Poland (-1, 4%) continued their budgetary adjustment process (which we had already succeeded but abandoned). The only one that has regressed with us, but not so much, was Hungary, which went back with the deficit increase (after decreasing to only -1.6% in 2016, it reached -2.2% in 2017)

Latin by nature, the same as the French-Spanish-Italian-Portuguese group (which shows that we should first work on adjusting society’s mentalities, before succeeding in the financial discipline), Romanians graciously missed (just like Balaci player in the match with Benfica in 1983, when Universitatea Craiova team passed by the historic chance of playing in UEFA Cup final) the opportunity to obtain a financial performance and lay the foundations for a solid development in the future.

When you see that all EU colleagues, from ex-socialist to Latin ones, willy-nilly comply with the German model, it may be a signal. Even on the rationales that ten persons say you’re drunk and then it would be more prudent for you to go to bed than keep driving.

Even Balkan Greece had to seriously tighten the belt after the carnival of deficits previously accumulated following reckless spending and has now reached an unlikely (for this country but also for us) excess of public finances. Which shows that the bill of momentary populist excesses comes implacably in time and for a long time.