The long-term interest rate fell below zero in the Eurozone and dropped to only 0.28% on average at the EU level, half as compared to the previous month and a quarter compared to March 2019.

No less than 13 states of the European Union have recorded negative values at this indicator, which shows the level that costs of financing the public debt can reach in the long term.

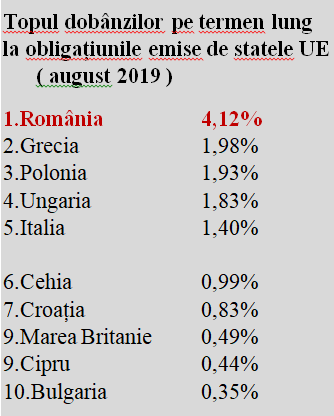

Although the yield obtained for loans granted to Romania decreased from almost 5% in April – May 2019 (4.91% and 4.93%) to 4.12% in August, the situation compared to other EU countries has significantly worsened in the last months:

Currently, we have reached more than double interest rates for Greece, Poland or Hungary and triple compared to Italy.

*

Ranking of long term interest rates for bonds issued by EU countries (August 2019)

- Romania

- Greece

- Poland

- Hungary

- Italy

- The Czech Republic

- Croatia

- The UK

- Cyprus

- Bulgaria

*

These four states, along with us, are the only ones that exceed the 1% threshold, below which the Czech Republic and Croatia, which recently applied for the Eurozone membership, rank. Our neighbour from the south of Danube, Bulgaria, also on its path to the single currency, recorded a value of only 0.35%, almost 12 times lower than us.

For reference, we also mention that Germany (-0.65%), Denmark (-0.58%), Luxembourg (-0.54%) and the Netherlands (-0.5%) recorded the highest negative loan interest rates, followed by Sweden (-0.36%), Finland (-0.35%) and France (-0.34%). Obviously, investors’ perception and the understanding of trends in each country played a decisive role.

In this context, we recall that Romania has by far the highest inflation in the EU, 4.1%, significantly higher than Hungary (3.2%), Poland, the Czech Republic (both with 2.6%) or Bulgaria (2.5%). Greece, which managed to dramatically lower the cost of loans from 4.37% in October 2018 to just 1.98% in August 2019, had an inflation rate of only 0.1%.

Obviously, a better management of the Romanian economy, closer to Poland, Hungary or the Czech Republic (with which we have in common the floating exchange rate regime of the national currency against the euro but we do not have in common the high foreign deficits that we are facing) would have brought a better perception from international investors and consequently lower borrowing costs.

To put it simply, we continue to borrow expensive money from the market (less than a few months ago, but, compared to other countries, under even more onerous conditions) for consumption.

Instead of using the favourable long-term market environment with public policies aimed at leading to more favourable interest rates for useful investment projects at the national level.

The key phrase related to interests we are currently using is „LONG TERM”.

That is, we will have many years to come, even if we manage to restore macroeconomic balances, to continue to pay the bill for the past to levels PREVIOUSLY set, in a „long-term” past.