European countries have quite diverse pension systems in terms of financing methods but basically based on two models, Bismarck and Beveridge. The former is mostly based on contributions targeted to social protection, the second one on general fees collected.

European countries have quite diverse pension systems in terms of financing methods but basically based on two models, Bismarck and Beveridge. The former is mostly based on contributions targeted to social protection, the second one on general fees collected.

The result is that the Bismarck model tends to limit the redistribution of benefits between different categories of citizens’ incomes, while the Beveridge model inherently contains a redistribution of money collected.

Technically, the first aims at preserving the living standard of those who contribute based on certain contribution criteria, while the latter aims at ensuring the subsistence by a uniform standard.

Although necessary for understanding the different situations in the practice of different states, these considerations are theoretical.

In fact, no country has a pure Bismarck or pure Beveridge system, and there have been changes over time from one model to the other.

*

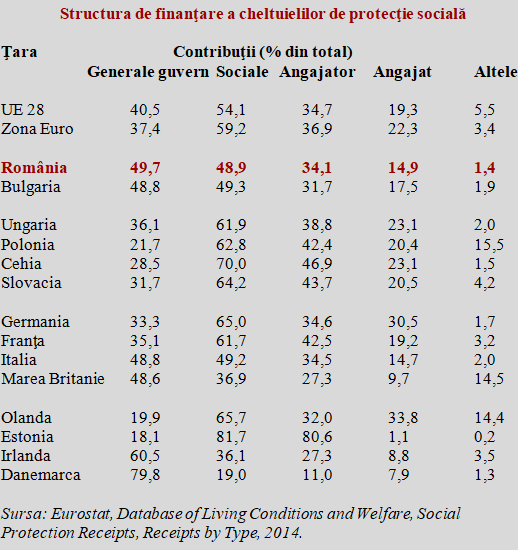

- Structure of financing for social protection expenses

- Contributions (% of total)

- General government social employer employee other

*

The most recent data available from Eurostat shows that the main source of financing of social expenses (where pensions have the „lion’s share”) were social contributions. They accounted for 54.1% of the total, compared to 40.5% of the general taxes collected by the government.

It is noteworthy that there is also a 5.5% part from „other sources” (which, pay attention, in our case, include the property taxes). In this chapter, not only the UK or the Netherlands have excelled, but also the country having the structure of the economy and the level of development closest to ours, Poland, all these above the 10% threshold compared to only 1.4% in our case.

Some northern countries, where government funding is predominant, are anchored in the tradition of the Beveridge system (where it is enough to be resident to be eligible for social benefits). Denmark (79.8%) and Ireland (60.5%) have the largest shares of government funding and, implicitly, lower social contributions (only 11% of the total in Denmark!). Also, Malta, Sweden and Cyprus have a funding share of over 50% representing sources of general contributions.

Other countries had rather chosen the Bismarck system, based on the concept of social insurance, where funding from contributions with this special purpose is predominant. Interestingly, Estonia is the champion of this type of approach (81.7% of the amounts come from social contributions) and other former socialist countries, Lithuania and the Czech Republic, surpass the country where this system originates, Germany (with 70.9% and 70%, respectively, versus 65%).

It is worth considering the Netherland’s approach, which has a share of social contributions similar to Germany, but it significantly supports the system by taxing the property and not just by general taxes, like Germany which does that almost exclusively (which has a share representing the „other sources” category similar to Romania and Bulgaria).

It is also worth mentioning Italy’s structure, which we overlap almost precisely. This shows that, beyond the strictly economic aspects, the decision in this matter essentially depends on the socio-cultural model deeply impregnated in the common origin.

On the other hand, if we compare to the group of countries from Central Europe, the data show quite clearly that Romania has a discordant note in terms of financing the social protection and it might be useful for us to take steps towards the convergence with these countries.

Finally, if we look at the employer’s share compared to the employee’s one (where Eurostat data have not yet integrated the transfer of social contributions almost exclusively to the Romanian employee, which obviously no longer happens in any EU member state) we see that (along with Bulgarians and Italians), we have applied neither the Bismarck nor the Beveridge system in a clear way, but an original employer/employee distribution, based on the principle „sure ain’t no one like us”. It is our sovereign right, but is that okay?