According to March 2020 data, the EC Convergence Report for Romania points out that the long-term interest rate for convergence purposes was 1.5 percentage points above the benchmark of 2.9% obtained based on the average of 0.9% recorded for the three countries considered (Portugal, Cyprus and Italy) plus two percentage points. Also with a very large difference of 510 basis points compared to the benchmark of the German economy.

According to March 2020 data, the EC Convergence Report for Romania points out that the long-term interest rate for convergence purposes was 1.5 percentage points above the benchmark of 2.9% obtained based on the average of 0.9% recorded for the three countries considered (Portugal, Cyprus and Italy) plus two percentage points. Also with a very large difference of 510 basis points compared to the benchmark of the German economy.

This indicator reached a peak of 4.8% in May 2019, a level recently reached again in April 2020 amid the pandemic (the value decreased afterwards, including due to the measures by the Central Bank on the secondary government securities market), after a decline to just 4.04% in February. Fortunately, even if with a close margin, we maintained our rating above the threshold recommended for investments, although with a negative outlook.

Complying with the level required by the euro adoption means a substantial reduction in interest rates applied on what we borrow in international markets. The most recent bond issues had good placement, close to the margin allowed, but are still „diluted” by previous investments, made with higher interest rates).

After missing this mandatory indicator for the adoption of the euro in 2017, we will have to restore macroeconomic balances relatively quickly and gradually bring it within the limits allowed by 2022 or 2023 (with the note that we will have to consider a safety margin because we follow a moving target).

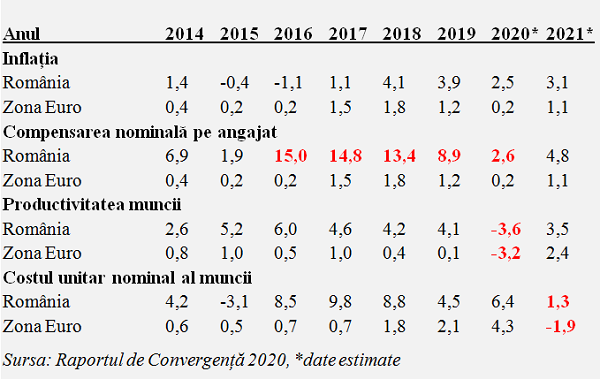

Inflation and labour costs

Another criterion for adopting the single currency, inflation, which should be at most one and a half points above the average of the three best performing Member States, was missed in 2018, but we are on the way to recovery, with a declining margin compared to the Eurozone, also according to the European Commission’s estimates (from 2.7 pp. in 2019 to 2.0 pp. in 2021, despite a certain resumption of the price increase trend).

Here we should make the connection with the nominal compensation per employee, which exceeded specific practices. It was well above recommendations for the macroeconomic balance, partly due to the relatively low starting level but also due to the necessary but too high increases in the public sector.

*

- Year

- Inflation

- Romania

- Eurozone

- Nominal compensation per employee

- Romania

- Eurozone

- Labour productivity

- Romania

- Eurozone

- Labour nominal unit cost

- Romania

- Eurozone

*

It is worth mentioning the level of salary increases, where we went up in 2018 to levels of 29.4% over three years well above 12%, the level recommended by the EC and by 60% above the second-ranked, Bulgaria (18.3%). In 2019, the provisionally calculated value decreased to „only” 24.9% but remains more than double the standard balance requirements, brilliantly met between 2011 and 2016.

The problem is that labour productivity will decrease this year but hopefully, we will manage to avoid getting below the average performance of the Eurozone, as seen in the EC forecast (-3.6% for Romania and -3.2% for EZ) . Of course, we will keep an advantage in the lower cost of labour, but its erosion will continue and competitiveness in a difficult market will be affected at the resumption in 2021 (we, with an increasing cost, Eurozone with a decreasing cost).

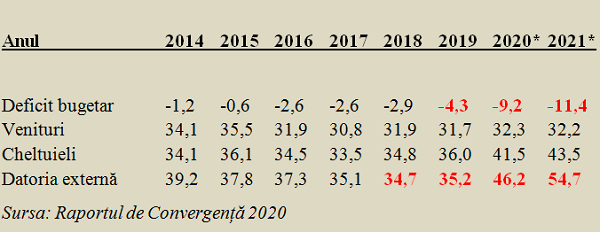

Budget deficit and foreign debt (% of GDP)

The third criterion missed in the attempt to access the euro antechamber in 2024 is the budget deficit. The other two economic criteria, the stability of the exchange rate has great chances to pass, given the stability of the Romanian leu exchange rate in recent years and the foreign debt share below 60% of GDP, a legacy of the socialist era, are still met and the legal criterion will be solved, the same as for other states that joined the Eurozone within the legal deadline.

*

- Year

- Budget deficit

- Revenues

- Expenditures

- Foreign debt

*

Thus, the nodal point remains the budget deficit and the exit from the excessive deficit procedure we entered in April 2020, even if for now we are allowed to exceed the 3% threshold to successfully overcome Covid pandemic. The basic truth is we can NOT increase social benefits at European levels without collecting European revenues to the budget and can NOT increase taxation when we want to get out of the crisis.

If we do not take into account the basic economic laws, we will bring public finances to failure, we will also miss, most likely in 2022, the criterion of debt below 60% of GDP. The EC already sees an increase of about 20 percentage points in Romania’s foreign debt in just two years, of a magnitude comparable to the previous crisis.

And it will not provide us with funds potentially estimated at around EUR 33 billion (EUR 19.6 billion non-reimbursable but for clear projects) for us to waste them with unsustainable Greek-like adventures. And that would happen no matter what politicians and short-sightedly approved laws would say, as they have no long-term vision and no connection with the economic situation in which they should be applied.

The economy, affected by the discrepancy between production and consumption

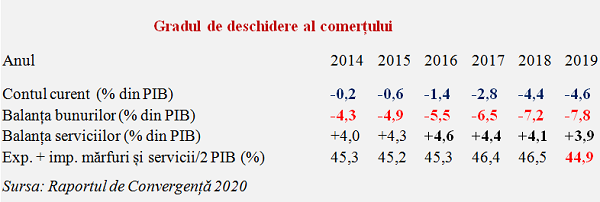

On the market integration side, it should be noted that, surprisingly, the degree of goods and services trade openness decreased in 2019 (meaning before, unrelated to the pandemic) to the lowest level in the last six years. To translate, foreign trade starts to miss the pace with the GDP growth, which, in the context of the deepening foreign deficit, calls for increased exports and/or better coverage of the demand from domestic sources.

*

- Degree of trade openness

- Year

- Current account (% of GDP)

- Balance of goods (% of GDP)

- Balance of services (% of GDP)

- Export + import goods and services/ 2 GDP (%)

*

Since 2014, the balance of goods has deteriorated, from -4.3% of GDP to -7.8% of GDP. The balance of services managed to partially compensate for this deterioration (there are also other components of the current account but we limit ourselves to the main ones) until 2016, after which neither did the services segment, despite all the contribution of the international transport and IT services, manage to keep up, reaching below 4% of GDP last year.

Nobody claims, as in the past, that we should produce everything at the global level and 5% beyond, but neither can we continue indefinitely with the growing gap between domestic demand and domestic production’s capacity to cover this demand, even with the benefit of the significant plus in the services sector.