In the absence of strategies to increase technological levels and raise wages, Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) will remain in the average income trap without any prospect of closing the gap with the West, warns Martin Myant, senior researcher at the European Union Trade Institute (ETUI).

In the absence of strategies to increase technological levels and raise wages, Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) will remain in the average income trap without any prospect of closing the gap with the West, warns Martin Myant, senior researcher at the European Union Trade Institute (ETUI).

The analysis takes into account the countries of the Visegrad Group 4 plus Romania (which comes from an inferior level but had similar economic growth).

In the 27 years of transition, these countries have developed economies dependent on foreign capital, where the main engine was the foreign direct investment (FDI) attracted by cheap labour.

This model has reached its limits and active state policies are required to stimulate a new structure of the economy.

That is why strategies with a two-directional impact should be developed, in Martin Myant’s opinion:

- to influence the type of foreign investment that will be made (to stimulate FDI for high added-value industries)

- to encourage autochthonous autonomous development to surpass the technological level of multinationals present in these countries

Dependence on foreign direct investment (FDI)

The first significant foreign investments came in the early and mid-90s when companies from abroad participated in privatizations started in the five states.

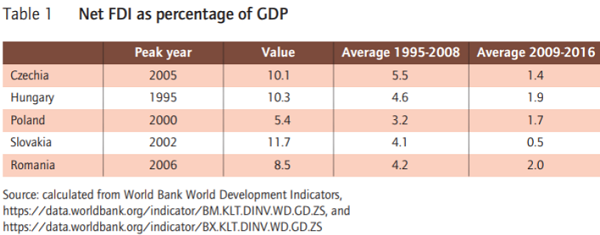

In all these countries, the peak moment (the year when FDI reached the largest share of GDP) was reached before 2008, the year that marks the slowdown in foreign capital inflows.

The pioneer was Hungary, where foreign direct investment accounted for 10.3% of GDP in 1995, a percentage reflecting the government’s preference to privatize companies by selling them to multinationals.

In the case of Poland, it is noticed that it was initially much more reluctant to accept foreign companies, and Romania is the last one to reach the maximum FDI/GDP (in 2006).

Between 2009 and 2016, Romania had the highest annual average – 2% of GDP, followed by Hungary, where the share was 1.9%:

In all cases, EU accession has not influenced the process, with multinationals anticipating it and having massive investments before. It can be seen even in the case of Romania, where the peak was reached in 2006.

In all cases, EU accession has not influenced the process, with multinationals anticipating it and having massive investments before. It can be seen even in the case of Romania, where the peak was reached in 2006.

The exception is the Czech Republic, where the highest FDI share of GDP was recorded in 2005.

Romania’s case – the worst

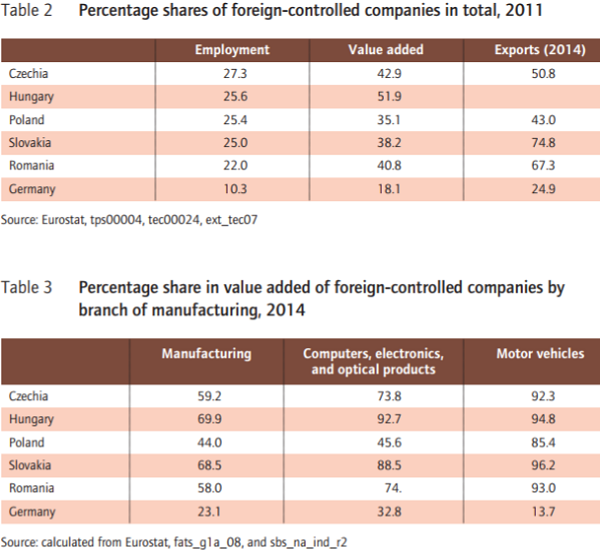

Foreign companies have become the major exporters in these countries and this way brought additional benefits. The main sectors where investments have been made are electronics and the automotive industry:

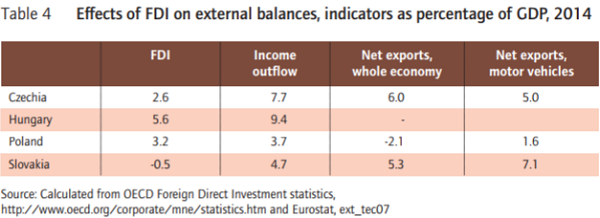

Over time, though, the positive effect of FDI has diminished and tends to be eliminated, as evidenced by the reduced impact of FDI in 2014 on the foreign balance (Romania is missing):

Over time, though, the positive effect of FDI has diminished and tends to be eliminated, as evidenced by the reduced impact of FDI in 2014 on the foreign balance (Romania is missing):

Romania, with even lower salaries than in the other four states, is a slightly different case than Visegrad 4 – here it has been relocated the production of goods for which factors such as highly qualified workforce or Western proximity matter less.

Romania, with even lower salaries than in the other four states, is a slightly different case than Visegrad 4 – here it has been relocated the production of goods for which factors such as highly qualified workforce or Western proximity matter less.

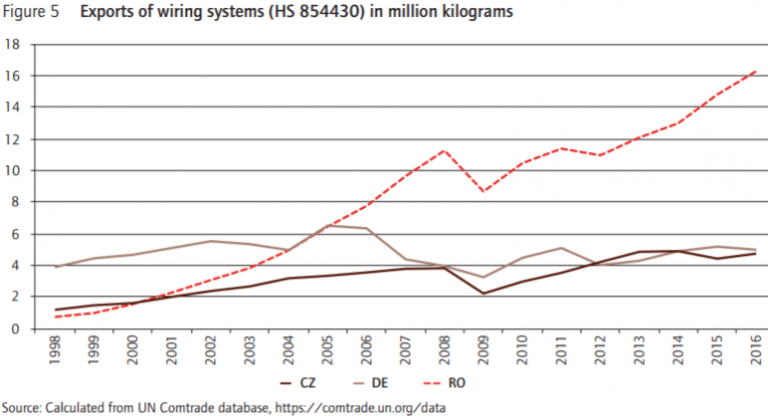

That is why Romania has come to dominate the car wiring sector. The volume of exports of such products has surpassed in time the Czech Republic (in 2001) and even Germany (in 2006).

The production of these wiring systems is the most mobile – they are relatively simple to do, do not require highly qualified personnel, infrastructure or significant investments, so that the activity can be quickly relocated to countries with cheap labour.

The production of these wiring systems is the most mobile – they are relatively simple to do, do not require highly qualified personnel, infrastructure or significant investments, so that the activity can be quickly relocated to countries with cheap labour.

This phenomenon even took place in the region, with closures of production in the Czech Republic and relocations to Romania.

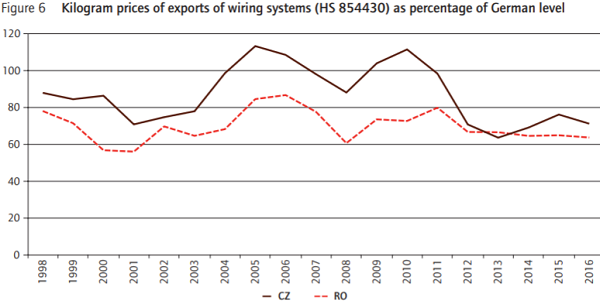

The data that Martin Myant analyses show that the price per kilogram of such product exported from the Czech Republic and Romania is below the one from Germany (although the quality is the same) and even decreased as the export volume increased:

Multinationals have transferred to a much lesser extent the types of production that require a high number of highly qualified workers and complex activities (such as research and development) are not expected to be moved to the CEE in the future.

Multinationals have transferred to a much lesser extent the types of production that require a high number of highly qualified workers and complex activities (such as research and development) are not expected to be moved to the CEE in the future.

For political and image related reasons, these will be maintained in Western states.

The consequence is that this type of dependency creates limits for the convergence process, does not ensure the progress towards a competitive economy (from a complementary one where we are now) and even threatens the stability of CEE economies (by increasing the risk of relocating the production to countries with lower wages).

Conclusion: Full wage convergence of the salaries can only be achieved if the income increases is accompanied by measures to create high value-added economic activity.

For this, there is a need for the state to take a strategic role to boost investment in skills, education and research so that we can reach an innovation-based growth.