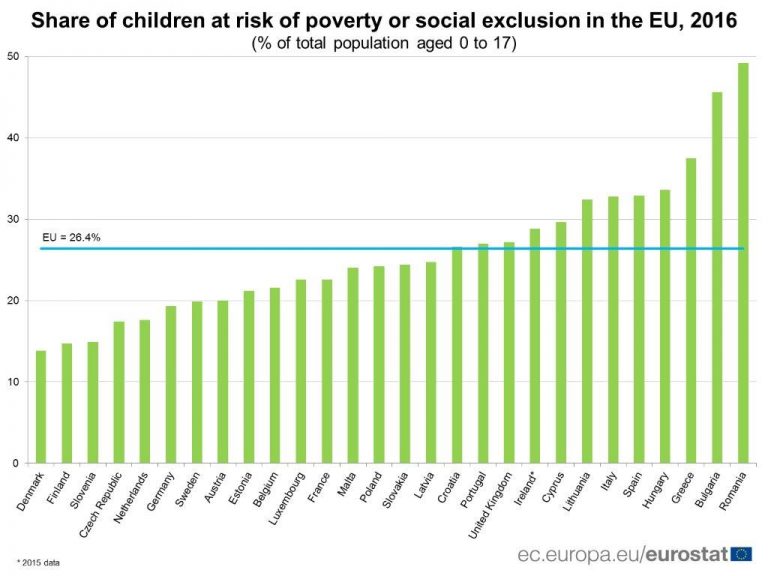

Romania continued in 2017 to be the EU member country with the largest share of children in poverty or at risk of social exclusion, according to data provided by Eurostat.

Romania continued in 2017 to be the EU member country with the largest share of children in poverty or at risk of social exclusion, according to data provided by Eurostat.

With a proportion of 41.7%, we have maintained the first position in this unwanted top of poverty, before Bulgaria (41.6%) and far from Greece (36.2%), Italy (32.1%), and Hungary (31.6%).

We should remember though, the improvement compared to the previous year was significant (in 2016 we had 49.2%, even above the level registered in the crisis period, respectively 48.1% in 2010) data refer to population aged between 0 – 17 years and the poverty level is one relative to living standards in each country.

On the opposite side, we see (somehow surprisingly) the Czech Republic (14.2%), which is slightly better than Denmark (14.5%), Finland (15.1%), Slovenia (also with 15.1% as the two Nordic developed economies) and the Netherlands (16.6%).

On the opposite side, we see (somehow surprisingly) the Czech Republic (14.2%), which is slightly better than Denmark (14.5%), Finland (15.1%), Slovenia (also with 15.1% as the two Nordic developed economies) and the Netherlands (16.6%).

The average recorded at the EU level was 24.5%.

Romania’s specificity: poverty, transferred from pensioners to children

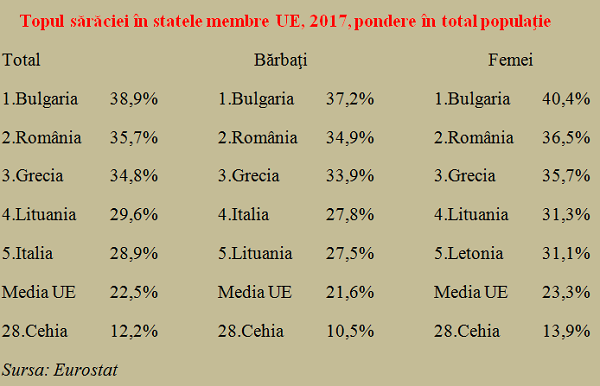

At the level of the total population, we rank second after Bulgarians, and this position is maintained both for men and women, even though the percentage is slightly higher in the latter, but this is a general feature that is also seen in the EU average.

Interestingly, the lowest values of this indicator are in the Czech Republic.

*

- Poverty ranking in EU countries, 2017, share of total population

- Total men women

- Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria

- Romania Romania Romania

- Greece Greece Greece

- Lithuania Italy Lithuania

- Italy Lithuania Latvia

- EU average EU average EU average

- Czech Republic Czech Republic Czech Republic

*

If we hold an unwanted first place in terms of youth poverty, Romania descents on fifth position in the age group of 65 and over, with “only” 33.2%, much behind Bulgaria (48.9%), Latvia (43.9%), Estonia (42%) and Lithuania (40.3%).

It is noteworthy the contrast between us and our neighbours from the south of Danube – we are below minus eight percentage points in the elderly category but „champions” in the youth category, they have the priorities upside down, namely with about eight percentage points of additional poverty in the group 65+.

Another major difference is that children count but they are not an important factor in the poverty level, while in our country there is a major risk for them to enter the category of disadvantaged population.

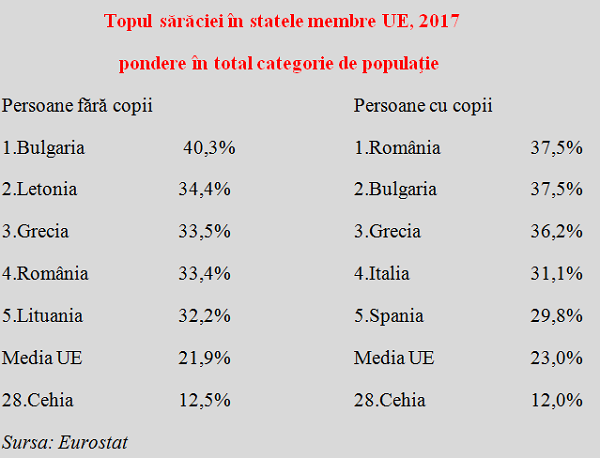

This can be seen from data provided by Eurostat, differentiated by people without children, where we hold the 4th place and people with children, where we get to the first position along with the Bulgarians.

*

- Poverty ranking in EU countries, 2017 – share of total population

- People without children People with children

- Bulgaria Romania

- Latvia Bulgaria

- Greece Greece

- Romania Italy

- Lithuania Spain

- EU average EU average

- Czech Republic Czech Republic

*

To our defence, we can invoke some cultural component that differentiate us at the European level, given the sudden presence in the Top 5 of the European poverty in people with children of some economies with a relatively high development level but against a background of some approaches of a Latin type, Italy and Spain.

Finally, the biggest discrepancy in positioning from a European perspective in terms of material shortages is found between the category of employed population and the one who does not have an income obtained this way.

*

- Poverty ranking in EU countries, 2017 – share of total population

- Employed population Unemployed

- Romania Germany

- Bulgaria Bulgaria

- Greece Hungary

- Hungary Netherlands

- Italy Lithuania

- EU average EU average

- Finland Poland

*

Here, we hold a clear first position in poor employees, but descend just on the 9th position in the unemployed category, where we are dealing with big surprises from some developed economies, such as Germany and the Netherlands (we remind that poverty indicators are relative to the national welfare level).

Altogether, it can be concluded that in our country, given the social conditions and the policies implemented, it seems to be better for pensioners than for youth, work is not a sure way out of poverty but its absence is not as serious, and having children is a major risk to personal well-being.