Romania has joined the European Union with the highest inequality in population incomes among the member states and continues to rank second, according to the data released by Eurostat.

Romania has joined the European Union with the highest inequality in population incomes among the member states and continues to rank second, according to the data released by Eurostat.

Instead of being part of the Central European group of former socialist states joining the EU, already aligned with the European practice, our country has teamed up with the BELL group, consisting of Bulgaria and the Baltic countries.

BOX

The way in which the population’s incomes are structured in a country can be mathematically expressed by an indicator called the Gini coefficient (by the name of the Italian economist who introduced it in 1912).

The values of this coefficient range from zero (if all citizens have exactly the same income) and 100, if a single person obtains all the available incomes.

The values of this coefficient vary from one country to another and within the same country over time.

The higher its value, the more unequally distributed the available incomes of the population, and vice versa.

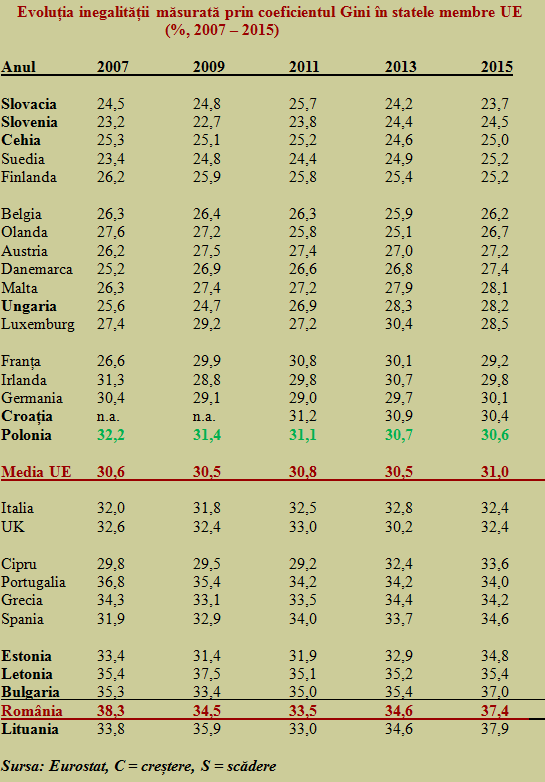

To be able to get an idea of how this indicator evolved at the European level, implicitly of the context where our country is placed, we present in extenso the data recently published by Eurostat, which shows how the distribution of incomes changed in the EU countries between 2007 – 2015 (see table).

*

- Evolution of inequality measured by GINI coefficient for EU states (%, 2007 – 2017)

- Year

- Source: Eurostat, C= increase, S= decrease

*

It can easily be noticed that Slovakia and Slovenia, already members of the Eurozone, as well as the most developed country of the group under the controlled floating exchange rate regime, the Czech Republic (also based on the mentality induced by the socialist years) were placed at relatively low levels of the Gini coefficient, along with the Western champions of the uniform distribution of incomes, Sweden and Finland.

Hungary has maintained in the same group with Benelux, Austria and Denmark, although it tended towards an increased inequality over the last few years, while Croatia and Poland have just declined below the EU average (along with Germany and France) after their EU accession. The adjustment trajectory of the closest economy in terms of size and structure to us, the Polish economy, has been marked in green with the intention to serve as an adjustment model.

Starting from 38.3 when it joined the EU, Romania gradually declined, during the period of maximum impact of the economic crisis, until 2009, to 33.5, a more reasonable level from a European perspective, but then returned to high levels of social inequality, reaching an unwanted 37.4 in 2015. The only good news is a provisional value for 2016, estimated at 34.7.

Even so, we would be close to Spain, the large economy from the EU with the most prominent social inequality, more than two percent above Italy and the UK, and in a not so happy companionship from the economic perspective, with Cyprus, Portugal and Greece.

Under these circumstances, it is hard to believe in coincidence and in the fact that the increased inequality in income distribution does not affect Romania’s development perspectives, including the process of approaching the living standards of the country as a whole to the West and adopting the single currency.

All in all, ALL our colleagues from the former socialist bloc that have both the same currency regime as ours and economies of a similar size are positioned in terms income inequality degree below the EU average, while we were well above the European average, the same as the countries with a weaker economic performance, as well as smaller and less developed countries, forced to have their national currency rigidly related to a currency reference (the Baltic countries have already joined the Eurozone).

Obviously, we would need a much more consistent middle class to reduce the extremes and maintain the social cohesion among the rich and the poor. The stronger this class would be, the easier it would be to prevent social dysfunctions and take more effective measures to meet the population’s needs as extensive as possible.

The mix between a large mass of underpaid (beware, not so many in the public sector as in the private sector) and a small group of super rich (related to the level of country development) makes the national averages less relevant and complicates the management of the country’s development process.

Despite increasing the wages in the public sector and pensions and providing all sorts of assistance, combined with measures aimed at improving the business environment, social inequality remains high. That is because no measures have been taken to stimulate the middle class and the accumulation of many small fortunes through personal highly qualified work properly remunerated (including the management of own businesses).

The data show us the result of the relatively bizarre combination of left and right-wing policies. That alienates the underprivileged, detracts the normality and normalizes „unlimited” profitability. A model that will send us further from the safety of living standards and lifestyle from the West, in its successful form spread to the whole society.