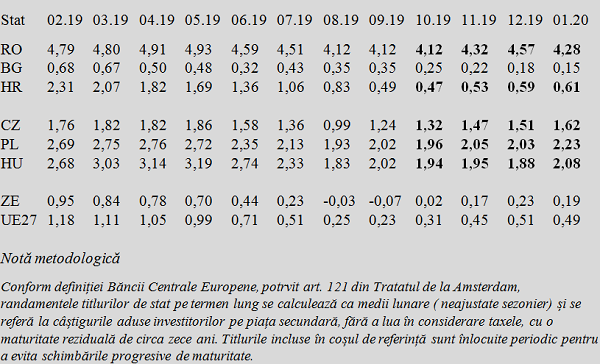

The yield of long-term Romanian government bonds was 4.28% in January 2020, according to Eurostat data.

The yield of long-term Romanian government bonds was 4.28% in January 2020, according to Eurostat data.

That is well above all the other states of the European Union and far from the European average of just 0.51% in the EU 28 configuration, which also included the United Kingdom until the end of January.

Some remarks:

Bulgaria can already access long-term money for development projects at interest rates below the Eurozone average and less than one third compared to the EU average (0.15% per year Bulgaria, compared to 0.19% per year in the Eurozone and 0.49% per year in the EU27-2020). With the note that Bulgaria has a public debt of only 20.6% of GDP (Q3 2019, reduced from 22.3% of GDP at the end of 2018!).

Croatia faces a public debt of 74.9% of GDP (Eurostat most recent data are from Q3 2019). Instead, it announced a firm intention to move to the single currency and applied a fiscal adjustment of the public deficit from -3.3% of GDP in 2015 to a surplus of + 0.8% in 2018 (again, most recent data certified by Eurostat), an evolution which is exactly opposite to Romania.

It is true that both Balkan states mentioned here had a cut in long-term borrowing costs by about four times over the last 12 months (Bulgaria from 0.68% to 0.15% and Croatia from 2.31% to 0.61%).

*

- Country

*

Methodology note: according to ECB’s definition, in line with article 121 of the Amsterdam Treaty, government bonds’ yield is calculated as monthly averages (not seasonally adjusted) and refers to the gains from investment in the secondary market, taxes excluded, with a residual maturity of about 10 years. Bonds included in the reference basket are periodically replaced in order to avoid gradual maturity changes

In this context, also Romania announced last year at the government level its intention to join the Eurozone sometime (2024 horizon was, from the beginning, less credible). But measures taken have led to an increase in budget and current account deficits. Which, even in the context of the monetary policy relaxation at the European level, only allowed a marginal decrease in the yields on long-term government bonds.

In the context of some contradictory statements regarding this critical indicator for public finances, we can refer to the development of foreign exchange regime colleagues in Central Europe with economies similar to ours by size.

The Czech Republic, Poland and Hungary, together with Croatia mentioned above, have been on a slightly rising trend in borrowing costs since October 2019.

Only that what distinguishes us is not so much the trend (otherwise sinuous) as the level on which this evolution took place in Romania, about two times higher than Hungary and Poland and triple compared to the Czech Republic, not to make an almost useless comparison with Croatia. Beware, with significant long-term effects, even if the adjustment to the financial equilibrium would start tomorrow.

This is the context in which we should carefully think about how long we can still borrow and at what costs, in order to be able to responsibly decide (including for future generations but also for the pensions to be paid ten years from now to those currently working) what would be and what would not be good to do with public money. Which can be borrowed in the long term under the conditions mentioned.